Photo-Illustration: Curbed; Photos: Michelle V. Agins/The New York Times/Redux, Gerald Herbert/AP, David Cantor/AP

Editors’ note: This essay was adapted from The Gods of New York: Egoists, Idealists, Opportunists, and the Birth of the Modern City: 1986-1990, by Jonathan Mahler, which will be published on August 12 by Random House.

A scandal-plagued incumbent. An Italian American from a working-class outer borough. A progressive front-runner looking to make history — and whom the real-estate community is determined to stop.

I am talking, of course, about New York’s 1989 mayoral race.

Let me briefly set the scene as primary day approached. The incumbent, Ed Koch, running for a fourth term, had led the once great working-class city back from ruin and presided over its transformation into the place we know today, a city whose economy is powered by finance and real estate. But his third term had been consumed by scandal — beginning with the mysterious suicide of the influence-peddling Queens borough president, Donald Manes — and social crises: AIDS, crack, homelessness, and a series of racial incidents whose names still resonate today (Howard Beach, Tawana Brawley, the Central Park jogger, Yusuf Hawkins). The Italian American, Rudy Giuliani, had been Koch’s chief tormentor; in his time as the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, his scalps had not only included plenty of city officials but also boldfaced names, including Ivan Boesky, Leona Helmsley, and Imelda Marcos. The front-running progressive, David Dinkins, was vying to be the city’s first Black mayor, promising to lift up those who had been left behind by the boom and to give voice to the voiceless.

Thirty-six years later, the echoes of that mayoral race are hard to ignore. Zohran Mamdani had not yet been born in 1989, but he grew up in the city whose seeds had taken root then, blossoming into what another mayor, Michael Bloomberg, memorably called a “luxury product.” Mamdani is vowing to transform New York once again, to return the power to working people. The choices before us as we approach the November election — status quo or social and economic upheaval — are wildly divergent. The moment may feel novel, even unprecedented. In fact, we’ve been here before. Some of you may even be old enough to remember it.

Having spent months trying to build a broad-based coalition of support across the city, David Dinkins shifted his focus in the final days before the primary to driving turnout among his base. His chief of staff, Bill Lynch, had deliberately not asked Reverend Jesse Jackson to campaign with Dinkins for the first several months of the primary campaign out of fear that the charismatic Jackson would overshadow his candidate. But Dinkins needed to galvanize Black and Latino voters in the homestretch. Jackson was more than happy to oblige. Dubbing the primary New York’s “Resurrection Day,” he formally endorsed Dinkins at a packed Black church in Downtown Brooklyn. “We want to pick up the broken pieces … recycle our anger into constructive energy and turn it into a new New York,” he said.

On the Saturday before the primary, Dinkins, wearing a white leisure suit, appeared with Jackson and Spike Lee at a rally in Jamaica, Queens. The next day, they were joined by Chuck D at the annual African American Day Parade through Harlem.

On Monday, the campaign’s final get-out-the-vote mailing landed in hundreds of thousands of mailboxes in Black neighborhoods around the city. “If we’re not in it, he can’t win it,” read one side; on the other were the lyrics to “Lift Every Voice and Sing.”

On primary day — Tuesday, September 12 — Lynch sent 200 sound trucks out across the city, as well as 10,000 leafleteers and 400 vehicles — buses, vans, and cars — to shuttle voters from housing projects and senior centers to polling stations. Jesse Jackson and a succession of other Black leaders were on the Black-owned radio station WLIB throughout the day, urging listeners to vote.

Dinkins held his final campaign rally that afternoon in the city’s whitest borough, Staten Island. He had nudged slightly ahead of the incumbent, Ed Koch, but Lynch knew better than to put too much stock in the polls. He had told his campaign about “the Bradley effect,” the phenomenon of white poll respondents not answering honestly when asked if they intended to vote for a Black candidate. It was named after the African American mayor of Los Angeles, Tom Bradley, who lost the election for governor of California in 1982 after leading his white opponent, George Deukmejian, throughout the race.

No one on the Dinkins team needed the history lesson. They had felt like underdogs from the beginning. Koch had been in office for so long and had loomed so large over the city — the joke went that “Mayor” was his first name — that it was impossible to imagine him losing to anyone, let alone a 62-year-old Black man.

Dinkins was skeptical, too. “Everybody knows that people lie when they leave the voting booth,” he told aides who handed him little slips of paper bearing encouraging exit-poll results in the afternoon.

By the evening, he was ensconced in the presidential suite of the New York Penta hotel with his family, senior staff, and a handful of close friends. When the polls closed, he asked for a glass of white wine and turned on the television. Moments later, it was official: He had beaten Koch. Jesse Jackson swept in with his retinue of bodyguards and embraced Dinkins, Lynch, and Harlem representative Charlie Rangel in a group hug, as the furniture inside the suite was hastily rearranged to make room for the TV cameras and spotlights.

A number of Dinkins aides, including a young Bill de Blasio, were still partying in the hotel ballroom hours later when the sun came up. “You all better get your shit together,” Lynch told them. “We haven’t won anything yet.”

Koch stayed in bed an extra hour on primary day. There was just one event on his ordinarily packed public schedule — “7:30 a.m. Votes” — and he needed the rest.

Four years earlier, he’d run virtually unopposed for reelection, the larger-than-life mayor who had presided over New York’s historic recovery. But it had all curdled over the course of his third term. The boom was over, the AIDS and crack epidemics were raging, crime was soaring, and the city was collapsing around him. Having once held sway over New York’s all-powerful Democratic Party, Koch had lost the support of all but the most conservative Democratic clubs in Queens and Staten Island. Local officials across the city who had endorsed him in 1985 were now abandoning him left and right, and Dinkins had locked up most of the city’s unions and nearly all its Black and Hispanic leaders.

And so Koch had taken his case to the voters himself, tirelessly hitting every event he could regardless of the size of the crowd or the likelihood that it would translate into votes. “Did you pack the Indian shirt?” he barked at an aide, as they hustled off to the India Day Parade. “I happen to be one of you,” he told a large group of senior citizens in the Bronx, noting that he was now, at the age of 64, entitled to $3 movie tickets.

For the last month, money had been pouring into Koch’s campaign from real-estate developers who worried that what had effectively been 12 years of tax breaks and zoning waivers were about to come to an end. The influx of cash enabled his campaign to blanket local TV with two new tough-on-crime ads, designed to shore up his support among the white working class. One featured a white police officer who had been shot and paralyzed by a Black teenager in Central Park in the summer of 1986; the other the head of the police union, who praised Koch for his support of the death penalty.

On the eve of the primary, Koch finally appeared in one of his own campaign commercials. He acknowledged that he had a tendency to talk too much and promised to try “to keep my big mouth shut.” But he also said that he loved his job and suggested, with uncharacteristic humility, that he thought he did it pretty well. Both the liberal New York Times and the conservative New York Post endorsed him, but he knew the city well enough to know that he could be in trouble.

Months of furious campaigning had culminated in a frenetic weekend — an endless blur of rallies, fairs, parades, synagogues, and churches. By the Monday morning before the Tuesday primary, Koch was so exhausted that he seemed to be nodding off onstage while waiting to deliver yet another stump speech.

He finally got out of bed at 6:25 on primary day. He was on another diet that called for a nutritional drink for breakfast, but he treated himself to a peach with his coffee. There would be no time for his usual morning walk on the treadmill with Barbra Streisand playing on his Walkman. He put on a gray suit and climbed into the back of his mayoral Cadillac, bound for his polling station: the Loeb Student Center at NYU. When the reporters waiting for him there told him that the last seven people in his voting booth all claimed to have voted for Dinkins, he shrugged off the unwelcome news. “I never do well in this district,” he said.

He spent most of the day in his office at City Hall, calling supporters to thank them for sticking with him and chatting with reporters, who found him unusually thoughtful and solemn. In the late afternoon, he retreated to Gracie Mansion. By now, he was receiving the same exit-poll data as Dinkins. He knew that it was all slipping away, but he tried to sound optimistic, suggesting that most of his voters would just now be getting off work and heading to the polls. “I feel I’m going to prevail,” he told reporters at around 5:30. But he could already see the concern — pity, really — on the faces of his senior staff. “Don’t worry about me,” he told them, repeatedly.

He was supposed to head to the Sheraton at 7:30 to await the final results, but he pushed back his arrival time an hour, as if hoping to postpone the inevitable. He was joined in the presidential suite on the 21st floor by a small crowd of his remaining intimates. Minutes after the polls closed at nine o’clock, the local news called the election for Dinkins by nearly nine points.

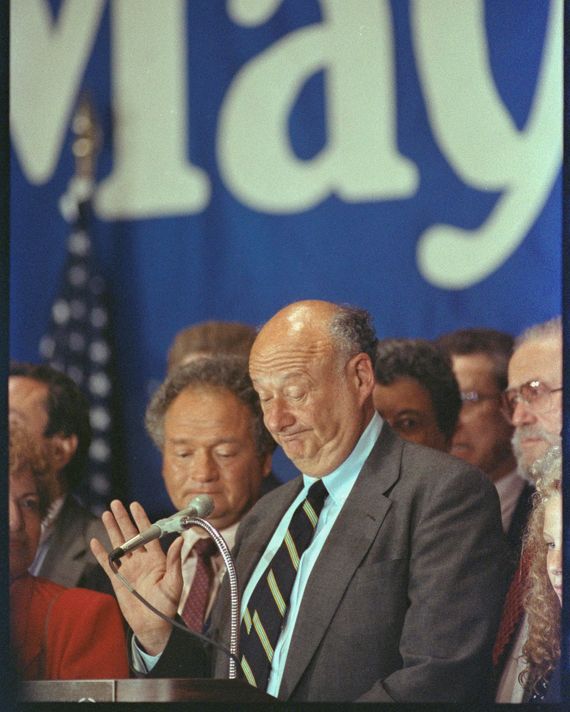

Koch put off his concession speech for as long as he could. Just as the city could hardly remember life without Koch, he could hardly remember life before the mayoralty. The job was all he’d ever needed or wanted. As he finally entered the hotel ballroom — arms raised, thumbs up — to the strains of Sinatra’s “New York, New York,” the crowd roared. “Imagine if we had won?” he said once the din had finally quieted down. “There is life after the mayoralty,” he continued, trying to both reassure his supporters and convince himself.

Koch concedes the primary on the evening of September 12.

Photo: Ray Stubblebine/Reuters

The general election was held a little less than two months after the primary, on Tuesday, November 7. It was Dinkins versus the former U.S. attorney for the Southern District — the prosecutor who would have been a priest, Rudy Giuliani.

Giuliani had entered the mayoral race in the spring as the prohibitive favorite. He was the hero of Wayne Barrett and Jack Newfield’s 455-page book about the Koch scandals, City for Sale, which hit bookstores in late 1988. Joe Klein published a glowing cover profile in New York, dubbing him “incorruptible.” The New York Post ran a cartoon of Koch imagining Giuliani sitting at his desk at City Hall — with a mounted trophy of Koch’s head above him. The columnist Jimmy Breslin, who was informally advising Giuliani’s campaign, publicly anointed him the next mayor. The Village Voice, of all places, observed that “Rudymania” was sweeping the city.

Giuliani had easily secured the Republican nomination in September, but the primary had been bruising. His opponent, the cosmetics heir Ronald Lauder, had spent a staggering $13 million on his campaign, much of it on negative ads casting Giuliani as a glory-seeking political opportunist. At the same time, Giuliani’s legacy as U.S. attorney was taking a beating. One of his most high-profile prosecutions, “the Pizza Connection” case — so named because it involved an international heroin-trafficking ring that distributed the drug through pizzerias — was crumbling on appeal, with a federal judge accusing the government of “ineptitude.”

Giuliani was a much less compelling figure on the campaign trail than he’d been at his news conferences at St. Andrew’s Plaza. As one columnist put it, he had “the demeanor of an undertaker and the verbosity of a lawyer.” The Village Voice’s Dan Collins wrote that if Giuliani “held up a baby, it might cry.”

Now that he was a political candidate, Giuliani was coming under increased scrutiny. He was outed as a draft dodger who had been spared service in Vietnam by a letter from a federal judge, and former colleagues questioned how much of his perceived success as a prosecutor was really just spin. The director of New York’s organized-crime task force punctured the mythology surrounding his fabled Mob prosecutions, going public with the fact that Giuliani had inherited the case and legal strategy from his predecessor. New York’s senior Republican senator, Alfonse D’Amato, called Giuliani a “publicity hound” who had abused the power of his office to build his reputation. “It becomes a question of a person who will go to any length to aggrandize himself, regardless of the guilt or innocence of a person,” he said in one TV interview.

Giuliani was inflicting plenty of damage on himself, too. Ignoring the warnings from his campaign staff, he responded indignantly and at length to every attack, keeping negative stories alive for weeks, and inviting still more criticism. Koch called him “hysterical” and compared him to Salome, the seductive princess with her dance of the seven veils: “Every time you take a veil off, you find some putrescence.”

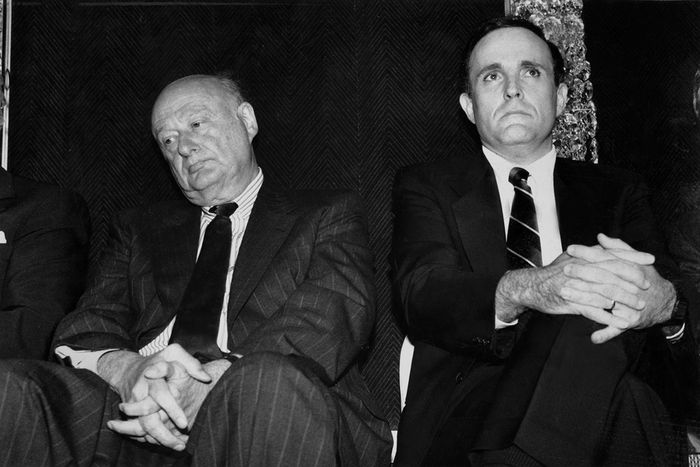

Giuliani and Koch at an event where they pledged to run a bias-free campaign, June 12, 1989.

Photo: Harry Hamburg/NY Daily News Archive/Getty Images

Even President Bush’s appearance at a Republican fundraiser at the Hilton in Manhattan in late June had ended in embarrassment when he mispronounced Giuliani’s name twice — “Ger … Giovanni … Gerlani” — before finally giving up and just calling him “Rudy.”

Giuliani’s campaign strategy had been to create a left-right “fusion” candidacy, positioning himself as a law-and-order Republican on crime but a liberal on a host of social issues including homelessness and AIDS. But it quickly became clear to his advisers that he wasn’t comfortable playing the progressive. And that he wasn’t really sure what he believed in, and what he didn’t.

By the end of July, Giuliani’s once comfortable lead over both Koch and Dinkins had evaporated. Alarmed, he turned to Roger Ailes for help. Ailes was one of the hottest political strategists in the Republican Party, a master of negative campaigning who had helped steer George H.W. Bush to victory in ’88 by casting his opponent Michael Dukakis as soft on crime. In the words of Newsday, his new job was to put “the White Knight back atop his horse.” Ailes got right to work, quickly creating two fresh slogans for the campaign: “Crime, Crack, and Corruption,” and “Rudy to the Rescue.”

To Breslin, the hiring of Ailes signaled not Giuliani’s potential renaissance but his certain demise. He stopped offering Giuliani advice and reversed his prediction for the election: “In the City of New York, the presence of Roger Ailes anywhere except on the highest hill on Staten Island could ensure that his candidate will lose to any Democrat who can walk.” Giuliani started the general-election campaign trailing Dinkins by as much as 34 points in some polls.

Ailes took firm control of the messaging with a clear strategy in mind. They would tack hard to the right and bypass the Black vote altogether. “Rudy’s going to get one percent of the Black votes by mistake,” he told reporters. Their narrow path to victory was to persuade Koch’s white voters to switch parties. This meant abandoning the progressive rhetoric that Giuliani had adopted in the primary and focusing squarely on crime. It also meant aggressively courting Jewish voters, who represented about 20 percent of the city’s electorate. And so Giuliani campaigned at kosher delis and senior-citizen centers across the Bronx and Queens with the Borscht Belt stand-up Jackie Mason by his side, and issued an only-in-New-York dog-whistle appeal to religious Jews via a full-page ad in a weekly Yiddish-language newspaper that pictured Dinkins beside Jesse Jackson.

It was an Ailes dictum that the media couldn’t resist a negative story, and for weeks he and Giuliani filled the papers with them. They attacked Dinkins for quietly hiring the controversial Black nationalist Sonny Carson to help get out the vote in Brooklyn; dredged up the old controversy over his failure to pay his taxes on time; and accused him of undervaluing his shares in a Black-owned cable company, Inner City Broadcasting, when he sold them to his son to avoid a conflict of interest after being elected Manhattan borough president in 1986. “The question is whether David Dinkins can drag himself across the finish line with his integrity around his ankles,” Ailes told reporters.

Giuliani embraced the strategy, easing comfortably into the role of politician as prosecutor. “Now let’s see if David Dinkins is given special treatment again,” he told a group of police officers after he and Ailes went public with their accusation about Dinkins not properly disclosing to the IRS his sale of Inner City stocks to his son. “For you and me, this would mean an investigation, possibly prosecution.”

Dinkins tried to shrug off the attacks, but Ailes was right: The media couldn’t resist a negative story. And so Dinkins found himself on the defensive for days on end. He eventually responded to the onslaught of attacks with an open letter to Giuliani threatening to retaliate with negative ads of his own. “I am determined not to let your consultant Roger Ailes do to me what he has done to other Democrats in other races, slandering their records and playing upon fear,” he wrote. “You and Mr. Ailes may have bullied people in the past. But if you persist on your present course, you will learn something I learned in the Marine Corps: Marines aren’t very good at picking fights, but they certainly know how to end them.”

For seven months, Dinkins had been focused on building a citywide coalition that could defeat the seemingly invincible Koch. But he was no longer running an insurgent campaign against an incumbent; he was now the official representative of the city’s Democratic Party. The message of healing that had animated his primary campaign gave way to more practical imperatives, most prominently, preventing Koch’s white voters from defecting to Giuliani. This meant publicly keeping his distance from Black activists and Black-owned media outlets. It also meant not campaigning with Jesse Jackson.

Dinkins responds to his supporters after his win on November 7, 1990.

Photo: Luc Novovitch/Liaison/Getty Images

Some Black politicians and pundits privately grumbled that Dinkins was taking his base for granted. But very few went public with their complaints. They accepted that this was politics. The city was poised on the brink of history, and they didn’t intend to stand in the way.

It was the city’s closest mayoral election in more than 80 years. Giuliani lost by just three points, or 44,000 votes. He was disappointed, but not discouraged. Given how much he’d been trailing by at the start of the general election, the final tally almost felt like a victory.

With Ailes’s guidance, he had found his voice, merging his prosecutorial sensibility with a new political identity. He’d done well enough to prove that this was just the beginning of his political career. Pundits were speculating that he could challenge Mario Cuomo for governor, or even his nemesis Al D’Amato for Senate. But Giuliani and his inner circle were already plotting a rematch against Dinkins in 1993.

Giuliani’s supporters were far less sanguine about his defeat. While he was upstairs in his suite at the Roosevelt Hotel absorbing his loss, about 700 of them were downstairs in the ballroom, insisting that the election had been stolen by rampant voter fraud in Black neighborhoods like Bed-Stuy and Harlem.

When he addressed his supporters just before midnight, he was interrupted by furious denunciations of Dinkins and calls for a recount. “Quiet, quiet!” he shouted, but the catcalls continued. His 15-minute concession speech became a frustrating exercise in trying to control the anger that he and Ailes had helped unleash. “We’re going to unify behind the mayor of New York, aren’t we?” he asked, defaulting to a call-and-response attempt to bring his raging supporters in line. But even as he shouted “Yes!” into the microphone, hoping they would follow his lead, many of his supporters yelled “No!”

Dinkins takes the oath on January 2, 1990…

Photo: Keith Torrie/NY Daily News Archive/Getty Images/NY Daily News via Getty Images

… And Koch passes the torch.

Photo: Keith Torrie/NY Daily News Archive/Getty Images

From the book The Gods of New York: Egoists, Idealists, Opportunists, and the Birth of the Modern City: 1986-1990, by Jonathan Mahler. Copyright © 2025 by Jonathan Mahler. Published by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.