A harried-looking guy in glasses and a knit hat is worried about his dimmer. It’s not LED compatible, he says, standing in a store filled with what seems like every kind of lightbulb that exists on God’s green earth. Does this mean he has to change his entire lighting system? The shop’s owner, David Brooks, who is 70 and white-haired, is unfazed. He has the incandescent bulb that works with that dimmer in stock — no need to panic. The customer is audibly relieved: “I’d much rather do that.” Anthony James Jr., the employee at the cash register, has seen it before. “Everyone comes in asking about incandescents,” he tells me. “People don’t like to change.”

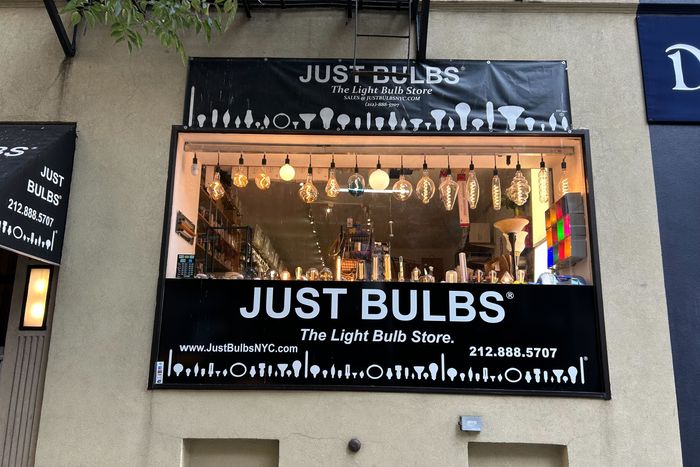

Just Bulbs, a small shop on East 58th Street with lightbulbs glowing warmly in the front window, sells exactly what the name suggests. You can buy a tiny bulb for a microscope, a smart bulb that’s compatible with your smart-home devices, or a set of colored bulbs for a party. There are old-fashioned Edisons and the tubular bulbs for hospital cafeterias and other places with unpleasant overheads. Just Bulbs is a long-running family operation (it first opened in Chelsea in 1980 before moving to East 58th), and Brooks is a third-generation lightbulb seller, but the shop has taken on new significance in the LED era. After more than 20 years of their slowly being phased out, the sale of most incandescent, halogen, and fluorescent bulbs was banned in the United States in 2023. As more and more of people’s go-to bulbs disappeared from the market, Brooks and his employees got better and better at figuring out approximations of the banned bulbs people were looking for — until those approximations were also banned. Today, he says, LED technology has gotten much better — “You can get LED lights now in eight different shades of white, so you can’t hate them all!” — but a certain set of people still refuse to switch their bulb allegiances. They can’t stand the new light and are desperate to buy old bulbs, even as they’ve become harder to find.

Photo: Clio Chang

Photo: Clio Chang

David Brooks showing off the lilac incandescent bulb he imports from Finland.

Photo: Clio Chang

Which is how Brooks became the go-to guy for illicit bulbs. As we chat, he shows off his different displays, which customers can turn on and off with a dial to test their worthiness. One wall is simply a floor-to-ceiling grid of plastic drawers, with more stacked on top, all containing bulbs. Brooks claims his is the only store he knows of that is legally allowed to sell these bulbs because he found an exemption in the law’s fine print that applies to small speciality stores to continue to carry stock that has otherwise been taken off the market. “I’m a former lawyer, and I read the law,” Brooks says. “I went through with a fine-tooth comb and found the exemptions. As far as I know, I’m the only one qualified in the country to sell them.” (He renews that exemption with the Department of Energy every six months but says no one at the department has been responding to his requests lately.) While Brooks acknowledges that you can find incandescents elsewhere — certain appliance bulbs remain legal, Home Depot still has some incandescents listed, and other sellers are trying to get rid of their inventory — his operation is uniquely thorough. Plus, he suspects these other vendors may be skirting the law a bit. “Of course, there are never any Department of Energy police walking around,” he says.

But more than just selling bulbs, Brooks specializes in finding bulbs. (While Trump says he will bring back incandescents and Republicans introduced the Liberating Incandescent Technology Act of 2025, the fact remains that most manufacturers have already stopped production.) “I’m a good hunter,” Brooks says of his methods. Companies go out of business and sell him their remaining stock, or someone switches to LEDs and gives him their extra incandescents rather than throw them away. Brooks has also become a master of niche inventory — the particular makes and models people want. One Just Bulbs employee tells me flight attendants from Europe used to stop in on their layovers when incandescents were first banned overseas. The store outfitted one woman from Nashville with a lifetime supply of a pink incandescent bulb that was particularly popular among older white ladies because, as Brooks tells me, “it hid the wrinkles.” She bought 200 for her house in Texas, 200 for her house in Maine, and extras for a wedding gift. Brooks can easily calculate a lifetime supply for someone based on the bulb’s lifespan and the number of lamps in their house. “And then, of course, you have to figure out how many years you plan to live,” he adds. When the pink bulbs ultimately ran out, Brooks advised customers to switch to a soft-lilac bulb made in Finland that mimics the same glow. He warns that bulb, though, may soon be gone as well.

Just a week ago, Brooks sourced a fluorescent pretzel-shaped bulb for someone with an outdated light fixture. He proudly pulls one off the shelf to show me — a neat twist of tubes sealed in ancient GE packaging. Brooks scoured the internet and asked around until he found another lightbulb company with a few in storage that it couldn’t sell. He bought them for a “fortune,” he says, and in turn the customer bought them from him for a fortune — six pretzel bulbs at $45 apiece. Brooks knows this is all a limited-run kind of operation. “Eventually the lightbulb business will disappear because LEDs last 15 times as long,” he says. “And newer light fixtures don’t use lightbulbs at all; they have chips in them.” He’s okay with that — he isn’t encouraging anyone to take over the business when he retires.

As for the lightbulbs Brooks uses at home? He tells me his favorite color of light is 3,500 kelvin, which he calls “Florida sunshine” — like standing outside on a clear summer day. “You can’t get that color in incandescent,” Brooks says. “It’s LED.”