From the back of the townhouse: Zack on the deck in her woodworking space, Blair on the main family level, and Brett in their backyard.

Photo: Eliana Glass

Living Arrangements is a series about the lengths New Yorkers go to cohabitate.

Walking into Alana Zack’s Red Hook apartment, you have to navigate around a pile of plywood and tree branches in the narrow entryway. There are even more stacked at the top of the stairs. “I had a gardening gig this past year and accumulated a bunch of branches from clients’ backyards,” Zack says with a laugh. “I’m always collecting wood.” But there’s more than two-by-fours and branches lying around. Rounding the corner into the hallway, there’s a pegboard of power tools and custom shelves spilling over with cables and hardware. And on the open-air deck at the end of the hallway, she has a worktable where she sculpts wood, sometimes with the help of a chainsaw. At the other end of the hall is a living area with a kitchen that doubles as her painting studio. In between the two is her bedroom, where, she assures me, she doesn’t work.

Artists making do in their New York apartments is not uncommon, but most do not install a woodworking studio at home. You need a large space with good ventilation — that’s rare and usually expensive. Plus, you need neighbors who can tolerate the sound of power tools going for hours at a time. A one-bedroom rental in a townhouse doesn’t usually meet these criteria. It’s definitely not what Blair and Brett originally had in mind for the top unit of the townhouse they bought three years ago, where they live with their teenage daughter and dog. To help cover the costs of the house, they had planned to rent out the top floor, expecting they’d list it with the help of a broker and lawyer.

Then, soon after moving in, Blair met Zack at a coffee shop on the corner. While waiting on line, she noticed Zack’s sweatshirt from a Martha’s Vineyard fish market she’d just visited and struck up a conversation. Zack shared that she was working as a wood fabricator in a nearby shop and spending all her spare time in the neighborhood. Blair told her they were looking for a tenant, but the timing wasn’t good; Zack had just moved into a sublet in Bed-Stuy the month before. Still, the women exchanged numbers “just in case,” as Zack puts it. A couple days later, unable to shake her gut feeling, she reached out to Blair. Zack toured the unit that week, and by December, she was moved in.

Zack, Brett, Blair, in the shared space outside Zack’s vestibule, where the family stores some of their shoes. The couple’s dog sits on one of Zack’s sculptural wood chairs.

Photo: Eliana Glass

Zack didn’t initially plan to use her apartment as a woodworking studio; when she first moved in, she’d just started working with wood and was so busy at the furniture shop in Red Hook that she barely had any time (or space) for painting, her primary medium. Nearly a year after moving in, she quit her job to spend the summer at a woodworking school in Maine and returned to Brooklyn determined to make art full-time — still painting, but also expanding into wood. She joined a community woodshop down the block from her apartment and began to split a painting studio with a friend in Gowanus. She finally had the space to focus on her art, but now she felt scattered, both logistically and creatively. “I was going back and forth, like, ‘Where is the drill? Is it in the wood shop or the painting studio?’” she says. “I had to figure out how to divide my time between painting and wood.”

The solution was to find a place where she could work on painting and wood simultaneously, a real-estate white whale. But Zack soon realized she already had it: her apartment. Two years after moving in, she put her handcrafted sofa and dining table into storage and converted her roughly 170-square-foot front room into a painting studio. As for the woodworking space, she dedicated the deck to it. She was used to working outside anyway. “At the community woodshop, I would set up on the sidewalk outside to do power carving, but I felt like I was a bit in people’s way,” she says. Zack describes the deck as “the biggest room in the house” at about 300 square feet, and it was easy enough to move her shop table and an assortment of sawhorses and scraps out there. Everything is exposed to the elements, but when the weather is bad, she’ll stash projects inside by the door or hide pieces under the shop table (and the tree branches are fine in any weather).

Zack’s shop table, scattered with power tools and a work in progress, with more wood on the bottom level.

Photo: Liv Ryan

From left: At the top of Zack’s staircase, a wall lined with power tools, woodworking supplies, and a few hats and accessories. Photo: Liv RyanZack sits on one of her wood pieces while working on another project in the front room of her apartment. Photo: Liv Ryan

From top: At the top of Zack’s staircase, a wall lined with power tools, woodworking supplies, and a few hats and accessories. Photo: Liv RyanZack sit…

From top: At the top of Zack’s staircase, a wall lined with power tools, woodworking supplies, and a few hats and accessories. Photo: Liv RyanZack sits on one of her wood pieces while working on another project in the front room of her apartment. Photo: Liv Ryan

The changes happened slowly, over months. Periodically, she’d ask Blair and Brett for help carrying an especially large piece of wood up the stairs, or show one of them a project when they came up to fix a leak. She told them she’d be “working more upstairs” but didn’t ask them for permission to turn the apartment into a full-blown woodworking studio. Blair remembers that Brett was initially nervous. “When Alana mentioned putting saws on the deck, he was like, ‘Well, will they be loud?’ and I was like, ‘Go for it, it’ll be fine.’” She admitted, “There’s definitely a dynamic in our relationship where I’m a little more open-minded about things at first.” But Brett denied having any reservations. Instead, he said he was happy Zack was putting the apartment to good use. He can’t hear her working anyway since he doesn’t work from home, and both of the couple’s bedrooms are two floors below Zack’s. He did admit to being more laid-back about the arrangement knowing the upstairs unit will need a gut renovation one day. “If we wanted to take over the upstairs in the future, it would have to be flat-out redone, so she can go nuts up there,” Brett says.

Still, Zack’s woodworking unavoidably generates noise and dust. She tries to minimize these factors with a few common-sense guardrails of her own. “I don’t go out there too early or too late and angle grind for three hours straight,” she says. Weekend mornings are also quiet hours, and she stops using power tools when the sun goes down (there are no lights on the deck anyway). Besides Brett, who works outside of the house all day, Blair and Brett’s teenage daughter didn’t have much to say about the arrangement (perhaps because her room is two floors below the deck on the opposite side of the house). But Blair works from home twice a week and can hear Zack on the saw from her desk, which is directly below the deck. However, Blair says she welcomes the sounds. “I like to hear the work of art being made,” she says. “It’s nice to be reminded of bold ways of making things.” Blair mostly works on the computer doing digital product design, but, like Zack, she studied art as an undergraduate. Both she and Zack also grew up around artists, and both apartments are decorated with works by friends and high-design pieces. The neighbors haven’t complained either. A couple have asked Zack what she’s sanding or sawing, but she assumes it’s in good faith. “I’m friendly with a bunch of them, and some are artists, so I think we’re all in it together, making stuff in Red Hook,” she says.

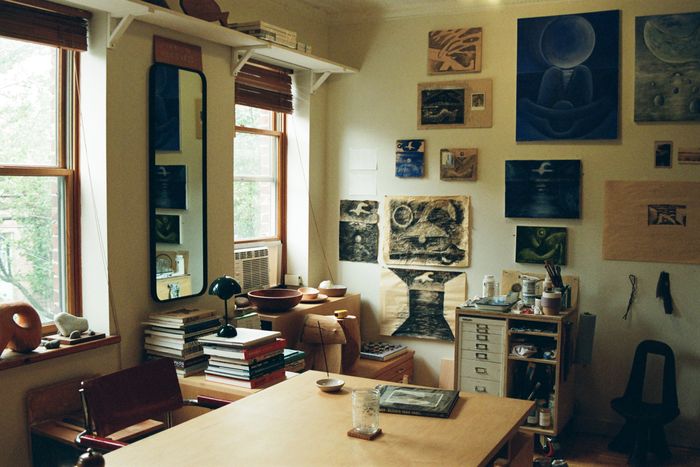

The home painting studio, mixed with furniture for the kitchen and living room, alongside a painting cart and works in progress on the wall.

Photo: Liv Ryan

Since converting her apartment, Zack has had far more time to work on her art. Last October, she had a debut solo show on the Lower East Side, and this November, a collection of paintings will be on view at a Red Hook gallery. “Having a home studio has preserved my focus,” she says. “I can work into the wee hours without having to walk under the BQE at 2 a.m.”

It’s been just over a year, and Zack’s woodworking schedule has yet to strain the relationship with her landlords. Along with checking in about the usual things — rent, repairs, and the lease — the three also find time to have dinner together at Café Kestrel and swing by each other’s parties. (They also refer to each other in casual conversation as “pals.”) The family almost always goes to Zack’s openings, and every couple of months, Blair helps Zack repot the window boxes in her unit. And whenever someone needs a favor — like taking in the mail or walking the dog — they usually text each other to ask. One winter, when Blair and Brett’s bedroom flooded, Zack spent hours helping them lift furniture and bail out water. “She was right there in the thick of things and didn’t think twice about it,” Brett says. “Kind of like family.”

Zack and the family in front of their townhouse, with one of her furniture pieces on display.

Photo: Liv Ryan

See All